Jonathan Ottke

Response

Between Islands

By Caroline Crawford

Inspiration piece

Good reading material for a long commute is important. Whatever you bring with you to read has to be compelling, but the kind of reading you can pick up and put down over and over again. This way, when you’re running for the subway, only to discover that the #4 express to Bowling Green just became the #6 local to Brooklyn Bridge, you can catch your breath and read for a few minutes until the next train screeches into the station, and you can still feel like you’ve accomplished something.

That’s why I started carrying poetry as I commuted back and forth from Staten Island into New York City.

“We were very tired, we were very merry–

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

It was bare and bright, and smelled like a stable–”

I looked up from The Collected Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. A stable, indeed. Seventy years after the poem was written, and the air was still hot and close and smelly, and I was tired–but not merry. What I was was drunk and sweating on in the Manhattan side of the Staten Island Ferry terminal. I hated the heavy bag of manuscripts on my shoulder, hated the panty hose that I’d been wearing since I had dressed for work over 15 hours ago, and especially hated the last beer I’d tossed back at the South Street Seaport, without which I probably would not have missed the 11:00 ferry. But instead I’d gone for one more round, drinking with some college friends like we had class and not work the next day, and now here I was with an hour to kill before the next ferry arrived.

The terminal was slowly filling with the remarkable variety of people that late night public transportation brings together in New York: burned-out Wall Streeters with their jackets over their arms, quietly and methodically sipping cold beer from tall paper cups, rowdy high-school students wearing threatening expressions and misshapen clothing, smartly dressed middle-aged couples returning from their semi-annual theater forays, and blank-eyed parents with irritable, exhausted children.

The bright fluorescent lights shone white-green, buzzing from the high ceiling through 40 years of flies. Rogue pigeons, some with maimed or missing feet, soared and strutted through the building. I read each illuminated advertisement for banking, temporary employment, travel agencies and the dermatologist who proclaimed, “Torn Earlobe? I’ll fix it!” I hated it all.

Two months before, I’d been cool and proud in a heavy black robe on a brilliant, breezy spring day, accepting my English degree with honors. I was employed, ready to begin a glamorous career in book publishing in my native New York. Now I was five weeks into a job at Panton, a book behemoth that liked to promote the fact that they had been Nabokov’s first American publisher, although their current authors were more along the lines of Suzanne Somers. I was the editorial assistant to Tess Finney, an editor just eight years older than me who ran half-marathons every weekend and who started every sentence with, “I DON’T think you REALLY get what I want,” and then finished with a sigh and a turn on her heel. She had had three assistants in the two years before I arrived. The wall calendar in my cubicle waited at October 1990. It was June 1991.

“Hey,” said a voice behind me. My hand still clutched the poetry book, which I’d taken to carrying in front of me during my commute like a bouquet of garlic in Transylvania. I turned my sweating self to a short, stocky young man whose opened shirt revealed a variety of chains and pendants frolicking within a deep forest of chest hair. “Hey, didn’t we go to high school together?”

Vinny Andino. ”Hello, Vinny, how are you?” I hadn’t seen him since I kicked him off of the yearbook staff for stealing senior portraits of the girls he’d liked. I wonder if he’d remember.

“Hey, you kicked me off the yearbook, remember?”

“Oh…did I? Wow. That was a long time ago.”

“Hey, so, Laura, it’s good to see you. What are you doing now?”

“I just graduated. I’m working in book publishing. Great job,” I lied.

“Books, hey, that’s cool. I’m an accountant now. Got recruited my senior year from Saint John’s. Big Six–Ernst and Young. Good money. I don’t start till September, so I’m doing the summer thing now, you know? Got a summer share down the shore, going out a lot. Maybe I’ll see you around?”

“Well, yeah, sure,” I said. “But you know, right now I’ve got this manuscript thing to read. Good to see you.” I sank into a seat. Vinny Andino. A Big Six accountant. I decided to focus on ways to stretch my $16,000-a-year salary so that I could afford the commute to and from Staten Island via the bus, the ferry and the subway in each direction, lunch out twice a week at a “pay by the pound” salad bar place, and the probability of living with my parents for the next 10 years. A helpless frustration mingled with my beer high. Here I was, alone, still half-drunk, attempting to proofread a manuscript so that I might earn an extra $40 of freelance money and afford another night out like this one.

I turned back to Edna Saint Vincent Millay and continued reading.

“ But we looked into a fire, and we leaned across a table,

We lay on a hilltop underneath the moon;

and the whistles kept blowing, and the dawn came soon.

We were very tired, we were very merry–

We had gone back and forth all night on the ferry.

And you ate an apple, and I ate a pear,

from a dozen of each we had bought somewhere.”

So much for my theory of satisfying commuter reading. Even Edna St. Vincent Millay was eating fruit with a companion, and I was alone.

I straightened up. Alone by choice, I needed to remind myself. I’d broken up with Ethan after five years of being his girlfriend so that I could experience the thrills of adulthood as a single woman. The thrills had yet to arrive.

Take last week, for example. Faith Ferland, an editor at Panton who has a set of eyeglass frames to match each of her outfits, approached me on Tuesday.

“Laura,” Faith whispered, sitting on the edge of my desk, her bottle-green eyeglasses perched at the end of her sharp nose, “Rumor around here has it that you’re single.”

“Well, as a matter of fact I am,” I said eagerly. I was relieved to be taken away for the moment from the pile of rejection letters that I was typing. “Dear Mr. Copeland,” said the one in my typewriter, “Many thanks for sending us Key Largo Nights. Unfortunately, we have found the market for fiction about the Drug Enforcement Agency to be challenging at present. Best of luck placing your manuscript elsewhere.” I turned to Faith. “I had a boyfriend all through college but I broke up with him before graduation. What do you have in mind?”

“Well, that’s just great!” said Faith. “My husband’s nephew just moved to the city. I’ve only met him a few times, but his name is Ted and he really he doesn’t know a soul. You seem friendly. Would you mind if he gave you a call? He’s got a great job–I’m sure he’ll show you a nice time.”

Night on the town in New York–this is the life I was waiting for, the kind of life I’d read about in Cosmo. A fabulous new dress, dinner, dancing, champagne on the promenade, dawn over the Brooklyn Bridge.

“Sign me up,” I agreed.

Ted called while I was at lunch and left his number. I called back eagerly. “Hi, Ted, this is Laura Shepherd. Faith…”

“Hello, Laura,” said a disarmingly smooth voice.

“Faith … uh.. Faith…uh… hi.”

Ted made the phone call mercifully short. Yes, his aunt had encouraged him to call. Yes, he had just moved here from Philadelphia and he didn’t know anyone. He was working as a vice president for financial research at Merrill Lynch. The hours were a bitch but the pay was great. He didn’t know much about publishing, but he’d be willing to listen if I’d be willing to talk. Yes, he’d like to go out Friday night if I was available. I was. Great.

“Ted,” I ventured, as we were getting off the phone. “How will I know it’s you? What do you look like?” We were scheduled to meet for a drink at Cafe Iguana on Park and 23rd. If we hit if off, we agreed, we would take it from there.

“Oh, back in college my friends told me I look like James Taylor,” he said. “I’ll wear a red tie.”

I arrived at the Iguana Thursday night looking for Sweet Baby James, but I instead found myself facing a sea of masters of the universe in red ties, one of whom looked disconcertingly like the James Taylor of 1991, complete with shiny bald head. I acknowledged him with a nervous wave and he gestured me over to his table.

Within minutes, Ted was deep into a description of financial strategies and a second glass of 15-year-old scotch, which I estimated to have cost close to what I made in a day. I was seven when they put that in the bottle, I thought, anxiously sipping at a gin and tonic. I had flinched when the waitress asked me what type of gin I wanted. Two months earlier my friends and I had been in bars till 2 a.m., drinking pitchers of mixed drinks made with cheap booze that came in plastic half gallon jugs. The only gin that came to mind was Old Mr. Boston. My panicked look had obviously amused Ted, who suggested Tanqueray.

“How old are you, Laura?” he asked, draining his glass.

“Twenty-one. How old are you?” I replied. I knew James Taylor hadn’t had such a hairline at my age.

“I’m 34. So. Tell me–what is it you do,” said Ted, looking at his watch. The champagne and the sunrise over the bridge were going to wait, I could see.

“Well, I’m in book publishing. You see, I always loved to read and to write and I thought that working in publishing would be a good way to combine things I liked to do and make some money.”

“Do you make good money?” he asked.

“No.”

“Then why do you want to do this?”

“Because I want to be a writer,” I said. I had never said that to anyone before, but it was true. I might as well start saying it.

“Do you get to write?”

“No. Well, I write rejection letters.”

“Writers don’t make money, unless you get a hook. Do you have a hook? Like, what’s his name, Tom Clancy. He has a hook.”

“Tom Clancy is a hack,” I told him. “His editor has to take his manuscripts home and rewrite them from beginning to end.”

“Yeah, so?” said Ted, “He makes money.”

At the end of the hour, Ted yawned and said something about an early morning meeting. We headed out the door together, and he insisted on hailing me a cab. “Nice to meet you, Laura. You’re a little young, but you’re a nice girl,” he said as he closed the taxi door. “Take it easy.”

The cab turned the corner. “Can you let me out right here?” I asked in a small voice. “I don’t actually have enough money for you to take me anywhere.” I walked down to Union Square and took the N train to the ferry.

That was last Friday. Here I was, a week later, and I was still smarting over the comment about needing a hook. Did James Joyce sit down to write Ulysses thinking, “now what’s my hook? I’ve got to pay the rent?”

What if he did? Too much to contemplate. Where was my book? I opened it and read,

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spark to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love cannot fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone…

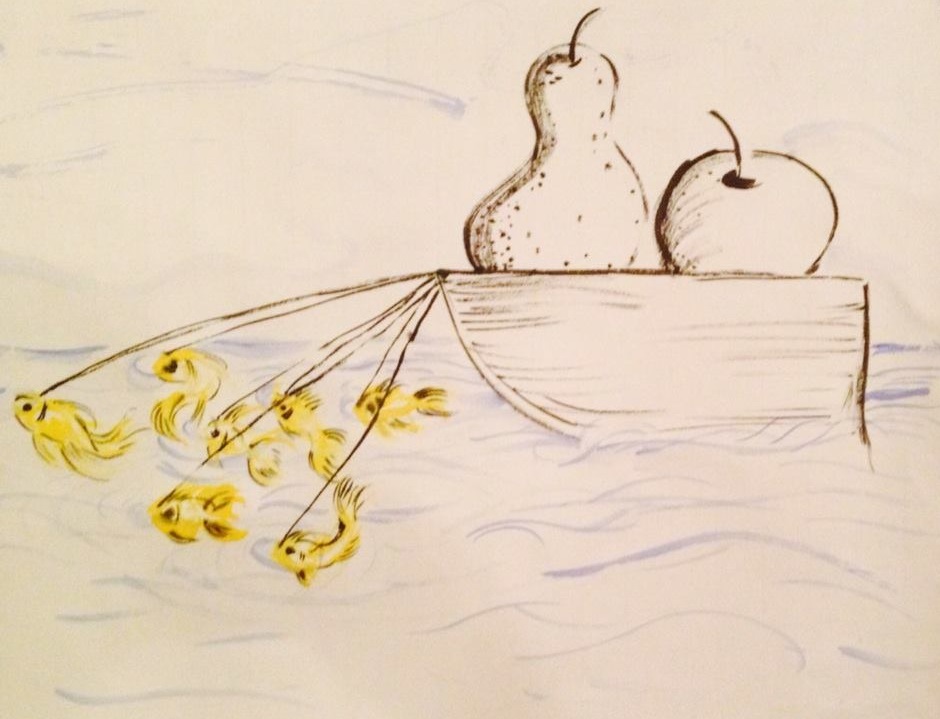

I closed the book. Nearby, a little girl began to whine. The large terminal clock loomed 11:45. The girl’s mother scolded her in Spanish and she started to cry. I put the book in my bag and paced, watching the girl, who was dressed in a dirty purple shirt and pink stretch pants. She began to bellow, then stopped. A young man was crouched in front of her, and, with a sketch pad on his knees, he began slicing lines of yellow, orange, blue and red across the page. I stood back, mesmerized like the child by the school of goldfish that were suddenly swimming on paper. The girl giggled, her curly brown pig tails quivering with delight, and she reached out a grimy hand and patted the fish. Her mother, heavy and dark and bluntly featured, suddenly softened. The young man spoke a few low words to the mother, then handed the girl the fishes and began packing his pencils into a square black case. The little girl squealed and waved the page in the air.

An artist. I surreptitiously watched the top of the dark grey baseball hat as his head bent into his case, deft fingers lining up pencils and erasers. An artist. Not an accountant. Not a financial analyst. Someone willing to sacrifice money and security for the love of work.

Finally the shining metal sliding doors to the boat slip rumbled open and the herds of commuters lumbered their way onto the ferry. I tried to keep The Artist’s cap in sight, but soon the crowds swallowed him up. I settled myself onto a long bench on the upper deck of the boat, next to a window, with Governor’s Island and Brooklyn glowing to my left. I was soon dozing, napping off the beer before I had to find my way home on the Staten Island side.

But the image of The Artist stayed with me, his cap disappearing into the sea of heads as that line repeated itself in my head. “Love is not all,” I recited. No, not all, but it mattered. To love what you do mattered. The ferry docked, and I stepped off the water, and onto land.

_________________________

Note: All of the art, writing, and music on this site belongs to the person who created it. Copying or republishing anything you see here without express and writing permission fro the author or artist is strictly prohibited.